Subtopic 1: Eating Out and Single Parenting

Growing up, me and my mom rotated around a set selection of restaurants. Among them was Blair Garden, one of our favorites which served mainly Italian style pasta. “Bueno sera!” I would hear every few days before being led to our table by my favorite server. He was tall and wore rectangular glasses along with the customary uniform that included a forest green apron, and was one of the few I remembered being there from the start. He would stop to talk if none of the other patrons required his immediate attention, and though I am sad to say I no longer remember his name, he knew mine as well as my order by heart; a trait shared among most all the servers. I always felt welcome at Blair Garden as a result, and even on the days I felt I could not bear to eat yet another serving of Italian food, I would agree to return yet another time.

Dinners were spent out of the house more often than not because of how work left my mom too tired to think about cooking. She was raising me primarily by herself due to my father living in a different prefecture to the one we were in. Despite single parents making up a growing percentage of households–12.3% and 23% in Japan and the US respectively–most of the people I told these old routines to who reacted in surprise grew up in dual-headed households, making me wonder what reaction I would receive if I instead talked to those who grew up in a similar situation to my own. In other words, is it more common for single parents to use the foodservice industry because of the extra responsibility involved? If so, is the experience changed in some way because of the location away from home?

Starting my research, I found my answer to the latter question first when the top articles recommended to me wrote not on the prevalence of eating out among single headed households but rather on family meals being important for their ability to bring family members together. According to Dr. Anne Fishel, a clinical professor of psychology and executive director of the Family Dinner Project, “The secret sauce of family dinner is the conversation and the games and the fun at the table,” and despite my version usually taking place in a restaurant, they still consisted of just that. After sitting down, (this time not at Blair Garden but at Lian, a restaurant serving breaded pork filets over rice) I would continue to talk about whatever was on my mind while grinding the sesame in the mortar and pestle placed at each of the tables in preparation to make my secret sauce to eat with my food. After ensuring that all the ground sesame was scraped back to the bottom of the mortar, I would proceed to add the prescribed sauce in addition to a few drops of salad dressing, water, mustard, and a sweeter sauce to make it the perfect balance of sweet, salty and tangy. It in a way was my own game that I played (though perhaps not the most respectful one at a restaurant). Even aside from this type of fun, my family meals were good for the number of times I had it in a week, which was around seven; the optimal number of times to reap the benefits which is cited to include improvement in grades, outlook on life, relationships with parents, body image, and eating habits as in addition to a reduction in substance abuse, teen pregnancy, mental illnesses such as depression, and eating disorders. I have very few if any memories of eating dinner completely on my own, for even if my mom was busy doing something while eating, she was usually still in the same room.

With the definition of a family meal more clearly defined with the core requirements being quality time spent with family over a meal, I looked next to how they are different across single and dual-headed families, beginning by looking at my own experiences living in the two types of households. Family meals with my mom I felt were very casual, though I do remember there being limited electronics usage, perhaps because of my own eagerness to talk rather than any specific rules set in place around it. In contrast, the family meals that I had with my aunt and uncle, or even my friends’ family (each of which I lived with over the course of my high school career in the States) felt a little more formal, in part because of these instances being one of the few times both head of household sat down together at a table. To emphasize the formality I felt at a family meal attended by two parents, I prompt one to think of how nervous they would feel if the food was taken away from a sit down dinner scene—a thought experiment which in the end yields a much more serious scene.

On another note, I think the formality also came from the intentionality inevitable in cooking at home and setting up the table for multiple people. Digging into the research done on the differences between single and dual-headed households, it was made obvious that the latter are more likely to view meals as opportunities to model healthy eating behaviors, with one father in an interview stating “…having a routine like a family meal every night makes kids get used to eating healthy, they just do it because it is part of their lifestyle.” It is probably easier for meals to be seen as more than an intake of nutrition for two parents, seeing how the main challenges facing dual-headed families eating together revolved more around time constraints, being tired, or running out of ideas as opposed to a lack of funds and the absence of another adult to help with cooking.

In fact, financial struggles seem to be rather common among single parents with rates of food insecurity being substantially higher for them compared to the national average. Such issues were particularly exacerbated during the year between March of 2021 and 2022, where many single parents were forced to skip meals in order to ensure their children were eating enough. One particular parent who was living off of government issued food stamps and spousal death benefits became ineligible for both after acquiring a job that paid $25,000 a year, leaving her monthly income $700 short of what she had before going back to work. Another parent was forced to go vegetarian due to meat generally being more expensive compared to fresh produce. In all, single parents report making an income 16% smaller and spending 8% less than the average; a statistic that was seen in nearly two thirds of food banks in America which experienced an increase in its client base.

Though information presented above does directly not answer the question of whether single parent households eat out more often, we are able to ascertain that they are most likely not having as many family meals due to their biggest barrier–financial limitations–being so prevalent among their social group even outside of inflation. This reasoning, combined with the fact that eating out is generally more expensive and requires more coordination with busy schedules, suggests that my experience of eating out every day is rather unique even within my others who grew up with one parent.

Image 1: Pictured is Blair Garden, the Italian restaurant mentioned in the above passage

Image 2: Pictured is Elizabeth Mendes Saigg, the single parent mentioned in the above passage who struggled to support her son, Khayonni, after the death of her spouse

Subtopic 2: Food and Affection

At one point late in my high school career, someone said that love is often expressed through the preparation of food in many East Asian communities. Though I do not remember if this was a person that I knew personally or a person whose work I was consuming, they mentioned the cutting and peeling of fruit, and the warmth and affection they felt when the act was done for them. It brought with it a sense of surprise, for I did not expect to realize the truth of this statement so far away from where I actually experienced it. However, looking at my memories through the lens of this discovery, many of my father’s actions revolving around the preparation of snacks and my favorite dishes started taking on a new light.

What I eventually concluded is that my father raised me too, more than I register most of the time. Even outside of being a parental figure by showing me the value of a gentle yet constant presence and remembering little details like the name of my third grade teacher, he was willing to come to the US for months at a time over the course of a year during quarantine to act as my temporary guardian, making him a single parent figure as well for a period despite the rather unique circumstances and the later timing.

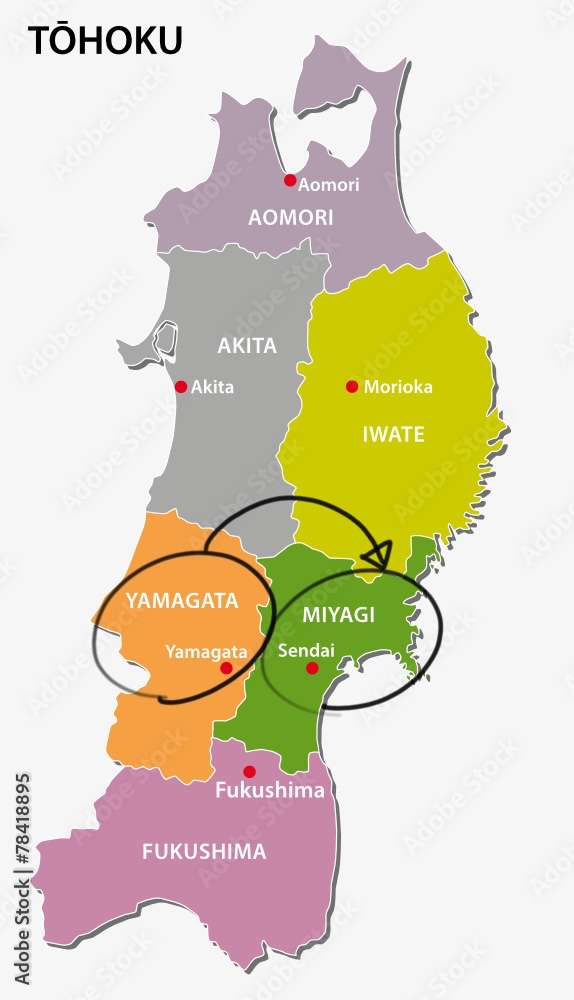

During this, he continued doing things like cutting slices of watermelon for us to have in between meals, but he also starting cooking more often, likely because we spent more of a substantial amount of time together, allowing for more time to be relegated to trying out different dishes, like spaghetti with a sauce using apples, and red bean sticky rice made from ingredients bought at the local international market. One recurring dish however was one I’d been having since I was little; a soup-stew hybrid called “Imoni” that is commonly eaten in the Tohoku region of Japan. The ingredients usually involve taro potato, konnyaku (a dense type of jelly), mushrooms, tofu, as well as thinly sliced beef. The flavoring actually differs between the regions Imoni is made in, and there is an ongoing debate between the prefecture my father lives in and the one I moved to over whether soy sauce or miso infused broth is superior. My father makes his with soy sauce, as is the tradition in his home prefecture Yamagata, and leaves it on the stove for only the time necessary for the potatoes to cook through in order to serve the soup as soon as possible. Despite the fact that my father has likely made other dishes that are equally as time consuming, it is this one that comes to mind whenever I think of food being used as a medium for showing affection, likely for the memories that are invoked of arriving at my dad’s house over the years to hear the bubbling of a pot and the slightly sweet and salty scent of Imoni broth wafting through the kitchen.

Realizing the symbolism surrounding food after having spent time with my dad meant that when it came my time to take over kitchen and meal prep duties, I did not consider it as a possible means to express my own affection in turn. Rather, what I ended up doing was going through the motions out of obligation, and I now worry that my father feels unappreciated as a result, especially considering how much more time I spend with my mom whenever I visit Japan for the summer. It brings to question how difficult it is, sometimes, to navigate expressing affection when the cultural standard on how it is commonly done is not intuitive to one’s normal methods. This cannot be a unique experience, however. As with any population, there are a myriad of different styles that people employ when it comes to love languages, which implies that conversely, there must be many others who share similar experiences of perhaps gravitating towards means outside of acts of service involving food. What then sustains this cultural standard in my opinion, is the fact that love languages are not as rigid as it is believed to be by many (a critique held by clinical psychologist Dr. Julie Gottman) and described to be by Dr. Gary Chapman, who is the original creator of the five love languages model. They can be learned, as anything can, especially when the particular action has a widely accepted meaning behind it. People engage in high fives for example, even if it is simply a clapping together of hands precisely because it conveys celebration and/or accomplishment.

My goal is, then, to convey my appreciation towards my dad when I see him this summer by trying my hand at making Imoni for the first time by myself. He taught me the recipe last year, and it seems only right that the dish which has brought me the most joy throughout my childhood is what I make for my first attempt at showing my appreciation for another person.

Image 3: Pictured is a bowl of soy sauce flavored imoni being served

Subtopic 3: Meals Together and Alone

There is a word in Japanese, Tanshin funin, that I heard often as a child. It referred to families (typically with children) where one of the parents moved away for work reasons. My situation was a little unusual because it was this but reversed, where one parent stayed while the other parent and child (me) moved. There is also the fact that the two are now genuinely separated in all ways but the law. However, what interested me about this topic is the prevalence of tanshin funin couples that are still together, meaning that many family meals in Japan are missing a member more times than not. These meals perhaps look like that of single headed households in the US, but with less worry for money and/or time considering the presence of two parents that can support the household. Meanwhile, the meals had with all members of the family present are likely more cherished. I myself saw this when I was younger while visiting my two twin friends on the weekend. When on normal occasions, usually during the work week, I would be welcome to stay into the evening, one day in elementary school I was told the family was busy for dinner because of my friends’ father coming home. I remember being surprised that he existed in the first place and gleaning the reason for him being away so much to be his work placing him in another prefecture for most of the week.

Looking however at the lives of the parent who lives away from home is feasibly the most telling of the causes behind Japanese work culture and population decline. These parents, often fathers, work late into the night due to not having anyone to go home to and preferring to work “rather than [sitting] and [staring] at the TV in an empty apartment.” They consequently have late night dinners that are often had out in a cheap chain restaurant tailored for late night customers, or at home with bento boxes bought at the nearest convenience store. The effects of this life away from home are only compounded by the amount of family time had together decreasing, and the children affected by these family dynamics growing up used to a more independent and work centered lifestyle with less opportunities to spend time with their spouses, which could facilitate the desire and decision to have children.

To conclude, we were able to see from this exploration how food and company are directly related. If one is in good company, they are increasingly likely to put more time and effort into the preparation of a meal, as can be seen in the effort it takes to prepare a child’s lunch everyday early in the morning contrasted with the lack of care put into food when one is alone, working away from home. Though this is not always the case, especially for those who do not have the means or resources to put care into the actual food, the effort in acquiring the food in the first place can also be a show of love for many parents. These are what makes family meals so significant in a culture; its ability to convey affection while simultaneously facilitating the strengthening of already established bonds.

Image 4: Pictured is a map of the Tohoku region of Japan. The two circled prefectures are Yamagata and Miyagi: the first of which I spent the early years of my life in until moving away with my mother to the latter prefecture.

Bibliography

Berge, Jerica M, et al. “Perspectives about Family Meals from Single-Headed and Dual-Headed Households: A Qualitative Analysis.” Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Dec. 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3871516/.

“The Crisis of Low Wages in the US.” Oxfam, https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/the-crisis-of-low-wages-in-the-us/.

Editor, Child & Family Blog. “Gender Division Disadvantages Japanese Children of Single-Parent Families.” Child and Family Blog, 24 Nov. 2022, https://childandfamilyblog.com/japanese-children-single-parent-families-disadvantaged/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20single%2Dparent,21.5%25%20in%20the%20UK).

“Food Security and Nutrition Assistance.” USDA ERS – Food Security and Nutrition Assistance, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/food-security-and-nutrition-assistance/?topicId=c40bd422-99d8-4715-93fa-f1f7674be78b.

“How to Have Better Family Meals.” The New York Times, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/guides/well/make-most-of-family-table.

Lindsay, Jo. “Challenging the Family Dinner Imperative.” Monash Lens, 2 Mar. 2020, https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2019/11/15/1378386/family-meals-challenging-the-importance-of-eating-together.

Wallace, Alicia. “Skipping Meals. Racking up Debt. How Inflation Is Squeezing Single Parents | CNN Business.” CNN, Cable News Network, 10 May 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/05/10/economy/single-parent-inflation-economy/index.html.

About the author:

Naomi Saito is a first year student who enjoys reading in her free time. Her favorite fruit is a custard apple or otherwise known as a Buddha head fruit, which she often shows people photos of when the topic arises (and sometimes even when it hasn’t).