Although it’s still nine o’clock in the morning, I feel terribly hot. The sun helps grow vegetables, but it just melts humans. Today, we are expecting a family of three coming from Tokyo to visit our farm. Since their three-year-old daughter had never experienced farming, we suggested that she could harvest red radish with us. She was delighted and engrossed in digging out one pink turnip after another. To make this moment more unforgettable, we prepared some of the turnips she had picked as souvenirs. However, the mother suddenly looked downcast and asked us with a faint smile, “Is it really, really safe to eat vegetables from this area? I’m not entirely comfortable with my daughter eating them.” Giving myself a little breath room, I explained the decontamination process of radioactivity and the inspection of food that I had even memorized. This has been a part of our daily life as farmers in FUKUSHIMA, as well as a manifestation of a serious social issue we all face.

Two pink turnips

Fukushima, in particular, Hamadori region (浜通り地方) is widely known for being affected by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Accident twelve years ago. On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake caused a 15.7-meter-high tsunami and damaged the enormous coastal area of the Tohoku region, including the nuclear power plants in Okuma, Fukushima. As the power plants used high-heat nuclear fuels, it was crucial to continuously cool the reactor core with water. The tsunami, however, destroyed the regular power source and its emergency diesel generators, rendering it impossible to remove heats or fill water. As a result, the water level dropped to the reactor core within a few hours, while generating hydrogen through a chemical reaction. It eventually filled the buildings and resulted in successive hydrogen explosions, the compound nuclear catastrophe the world had ever seen. This chain of events caused the release of a significant amount of radioactivity, such as Iodine-131, Cesium-134, Cesium-137, and Strontium-90; although the amount was later announced to be about seventeen percent of that of the Chernobyl disaster, people all over the world watching live news streams were puzzled and frightened.

The aftermath of this accident had a severe impact on the lives of residents. First and foremost, the government specified and gradually expanded the evacuation zones. Ultimately, the day after the earthquake, those living within twenty kilometers from the power plants were forced to leave their homes. Believing they would be able to return home in a week or so, the residents made minimal preparation and boarded a bus to be apart from the town semi-permanently.

Damage to the primary industry in neighboring areas was also profound. In fact, one week later after the accident, milk and spinach contaminated by Iodine were first found. The government and industrial groups soon requested over eighty-four thousand primary industry workers to restrict operations of agriculture, forestry, stock raising, and fisheries. Farmers suddenly lost their income sources, and the direct damage to vegetables and dairy products amounted to seven-hundred forty one billion yen (two billion five hundred million dollars) in total, which was almost three times the annual agricultural production value of Fukushima.

While allowing agriculture to resume little by little, the government strengthened various measures to ensure food safety. For example, it was decided that all rice produced in Fukushima would be inspected for radioactive cesium levels, and only rice that met the standard safety level were shipped. For the next eight years, around ten million bags of rice were examined annually. Decontamination of farmland was also carried out by the national and local governments in thirty-seven cities, towns, and villages. As most of the radioactive materials existed a few centimeters from the ground surface, clear-up activities were done by scraping a thin layer of topsoil and replacing it with a subsoil layer. Thanks to these enormous efforts, all the food produced in Fukushima on the market should have been guaranteed to be safe, thereby removing worries from consumers and distributors.

As a matter of fact, however, many citizens were deeply concerned that contamination had not been proven to be zero. They were suspicious of the “official” safety level for food which was set at “no more than 1 millisievert per year of radiation from radioactive materials in food.” It was too hard for the general public to understand its scientific evidence, so they feared the action of absorbing radioactivity itself. Combined with the loss of trust caused by the government’s numerous delays and failures in response to the disaster, the percentage of those who avoided food produced in Fukushima reached sixty-eight percent in 2013. In particular, people with higher income, higher education, more children, and those living farther away from the nuclear power plant were less willing to purchase it.

A defamatory message sent to the remote farmers market to sell products from Fukushima “Screw you! Don’t bring Fukushima’s food to Kyushu (our city)! Do you take responsibility if I become ill in the future? Have you truly examined all the products? Safety and compassion are different!”

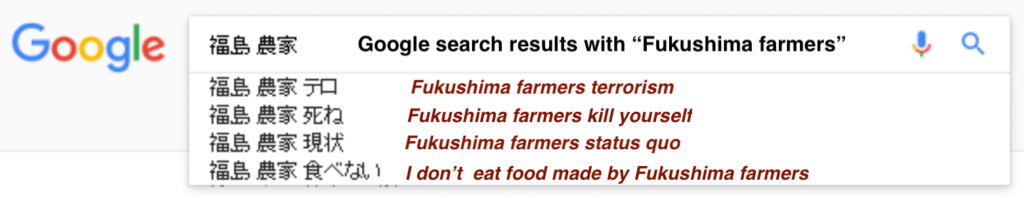

When you searched for “Fukushima Farmer” on Google, the suggested relevant words were “terrorism,” “kill yourself,” “status quo,” and “I don’t eat them.”

One summer night, I was intensely drawn to an article suggested by Twitter algorithm. It was a feature story about a man working to revitalize the food community in Fukushima. Reading about his passion reminded me of the world-shaking event that had occurred there for the first time in a while. I was happy to learn that some energetic people were initiating agriculture to revitalize it. But at the same time, many questions came to mind, such as how the radioactive contamination was being addressed now. As a Japanese citizen who would study abroad soon, I couldn’t help but want to see Fukushima with my own eyes and reflect on its events thoroughly. I got myself ready for a journey to live in Fukushima and intern on a farm there.

On April 3rd, 2022, I arrived in Nami-e, Fukushima. The town’s mainstreet was only twenty kilometers away from the nuclear power plants, and people had been allowed to return and live there for five years previously. As I looked at the scenery from the car, I noticed a stark contrast between the unnaturally new roads and the number of vacant houses. I learned that the reconstruction process after such a disaster was based on the pleasure of new developments and the sorrow of losing the past.

Then, I went to the “Nami-e Hoshi-Furu Farm” where I would be working for the next four months. The owner, Sayaka, was a kind and strong woman who was born and raised in Nami-e. She had returned to her hometown a few years ago and started a new farming business with Daiju, a former Japanese diplomat who had moved to the town to dedicate his life to the revitalization of Fukushima.

Standing picture of Sayaka(Left), Daiju(Center), and the author(Right)

The main field of Hoshi-Furu Farm

When I joined the team, Sayaka and Daiju were working on an extraordinary project to grow one hundred different crops simultaneously, with two intentions. The first was to accumulate data to alleviate the burden on future farmers. In those areas, products that had not been grown were required to be inspected before shipping. In other words, farmers who wish to cultivate new crops have to accept a risk that their whole income might be lost if their products were rejected for sale. Sayaka and Daiju hoped that future agriculture in Namie would not be intervened by nuclear disaster. The second intention was to send out positive news of farming in Fukushima to outsiders. Daiju believed that the shift in focus from fear of radioactivity to the attractiveness of the food was necessary for the further development of agriculture in the town. Leveraging his experience and networks as a marketer, he asked influencers and prominent chiefs to promote the products. To make the products even more appealing, they were even asking visitors to spread starfish in the field, which was said to be effective against wild boars that could damage the crops.

Although I was convinced of the value of gathering experimental data, I was doubtful about intentionally focusing on dispelling the doubts regarding food from Fukushima. It was a matter of fact that Fukushima’s food was controversial for some people, but I thought that there were no grounds for only caring about the six percent of those negative people. I believed that unless farmers could guarantee that the food was safe and make all the information accessible, they were better off not discussing their production.

No sooner had I started working, however, then I realized that my opinion was based on a biased perspective. As I helped Sayaka with her routine work, I understood the incredible amount of hard work involved in being a farmer, which helped me to see and feel what farmers were experiencing.

First of all, most agricultural practices were physically demanding manual work. As Hoshi-Furu Farm was pesticide-free, I had to deal with weeds everyday. Doing this exhausting but repetitive task always made me feel isolated, as the vast farm seemed to be never truly cleaned. My back, knees, arms, and hands were also sore every night from the strain. Furthermore, farming does not allow any breaks or shifts. Since we had to complete at least one type of work every day, such as watering, thinning, and adjusting to the weather conditions, it was impossible to leave the fields unattended even for a few days. As my parents were white-collar workers who had weekends off, the farming standard of endless work was quite shocking to me. Finally, the unpredictability of nature made farming a challenging job. While farmers rely on the help of nature to grow crops, it could be a threat at times, as natural disasters can quickly destroy the field despite all our efforts to protect them. During my time on the farm, I experienced multiple typhoons that caused almost-matured tomatoes to fall off the vine and spoil.

I found myself admiring farmers for their resilience and collaboration with nature over countless years. Their words and attitudes moved me deeply again and again. For example, Sayaka shared with me that farming was not just a job, but a way of protecting the land that had been home to her family for thousands of years for the next generation. I realized that the role of farmers in society extended far beyond just providing a source of sustenance; it was about enriching and sustaining all our lives through the invaluable act of nurturing life. I also became certain that farmers in Fukushima never hid behind anything, so everything they assured me to be safe was truly safe.

Tomatoes in Nami-e Hoshi-Furu Farm

Sprouts of Matricaria Chamomilla in Nami-e Hoshi-Furu Farm

After this, I could not tolerate the fact that Fukushima farmers were not receiving the recognition they rightfully deserved. The nuclear disaster was the externality of the commons for local people because a benefit of having nuclear plants was primarily experienced by far-away electricity users. Yet, urban consumers only recognized themselves as victims, imposing the burden and responsibility to repair the damages on local producers who, ironically, had long supported the development of the far-away city through food and electricity. I had an overwhelmingly uneasy feeling when I saw that the dedication of the Fukushima farmers was negated by urban consumers in the name of fear. I wanted them to know how much their careless words could hurt farmers’ hearts and have a negative impact on the market. This frustration finally made me understand the necessity of Daiju’s marketing effort to influence the consumer’s views radically.

In modern society where social roles are fragmented, people forget that they are indirectly involved in social problems. This can lead to loss of social cohesion, which is integral to collaboratively deal with public issues. When sociologist Émile Durkheim observed the industrialization period, he found that the increasing division of labor ended up increasing the superficial relationships of people within society, accelerating their indifference to those who are judged as “unrelated people”—like faraway farmers.

In an era where we are under an illusion that we can do everything on the Internet alone, we should again recognize our wide range of interconnected relationships. I believe that genuine support in an emergency cannot be fostered without having a sense that you are a part of the big community. In particular, food distribution, which is indispensable for all of us, needs to be seen as the outcome of various connections. Two thousand years ago, when people shifted from hunting to food production, they lived in small communities where food was exchanged and consumed with direct contact. In fact, in Toro, Japan, where rice paddies from that period still remain, only twelve dwelling sites are identified, meaning that all the process of cultivation, distribution, and consumption were concrete to residents. This kind of face-to-face communication, which has been regarded as the place for development of trust and gratitude, must be reborn.

I still appreciate my four-month stay in Fukushima which made me confidently say that food from Fukushima is the best and Fukushima farmers are the most honest and joyful in the world. By directly interacting with producers and experts to learn about their behaviors and core thoughts, I felt that I could see the real trajectory of farming in Fukushima as well as my position as a food consumer within the framework of the division of labor. If more people gain this kind of first-hand experience and learn about people far from their own role in society, we would be able to cherish the practice of eating food that also connects our body and the world more.

At the end of my journey, I met a young French chef who came to visit our farm. Seeing the perseverance of the farmers, he told us that he wanted to cook some French dishes with our products in a nearby kitchen. That night, the farmers, the marketers, and the community members were at the dining table lined with beautiful dishes that fully used our vegetables. It was a moment when all the people involved in the food were connected. I still remember the joy of asking and answering questions to each other, such as “Who produced these vegetables?” “What kind of method did you use?” What was the hardest thing to do when you cooked them?” I hope the day when this dining table spreads to the entire planet and people exchange their delight and gratitude with each other.

Bibliography

“2-2 米の生産量が増えて日本の人口も増えた(Japanese Population Increased as the Rice Production Increased).” 米穀機構. Organization to Support Stable Rice Supply. Accessed April 24, 2023. https://www.komenet.jp/bunkatorekishi/bunkatorekishi02/bunkatorekishi02_2.

Aruga, Kentaka. “Are Environmentally Conscious Consumers More Likely to Buy Food Produced Near the Fukushima Nuclear Plant? An Investigation from a Consumer Survey.” Environmental Information Science Academic Research Collection, 2014. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ceispapers/ceis28/0/ceis28_223/_pdf/-char/ja.

Durkheim Émile. The Division of Labor in Society; Being a Translation of His De La Division Du Travail Social. New York: Macmillan, 1933.

Kevereski, Ljupco, and Dean Iliev. “‘Face to Face Communication’ in Families – the Historical and … – Ed.” Research in Pedagogy, 2017. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1165888.pdf.

Motoshima, Yuzo. “東日本大震災及び福島第一原子力発電所事故による 農林水産関係被害と現在の課題(The Damage and the Obstacles of Agriculture after the Nuclear Disaster).” Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Committee, June 1, 2011.

Suga, Sota, and Kota Kawasaki. “Current State and Issue Concerning Revitalization of Agriculture from Nuclear Disaster in Fukushima.” Reports of the City Planning Institute of Jpan, 20, May 2021, 1.

Yoshida, Masataka. “福島第一原子力発電所事故以前の 津波高さに関する検討経緯 (History of Tsunami Height before the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident).” Science Council of Japan, August 1, 2017. https://www.scj.go.jp/ja/event/pdf2/170801-1.pdf.

“なぜ、福島第一原子力発電所の 事故が起こったのか?(Why Did Fukushima Nuclear Power Plants Accident Happened?).” Fukushima University. Accessed April 24, 2023. http://www.sss.fukushima-u.ac.jp/phys/why.html.

“原発事故 克明な放射線量データ判明: 40年後の未来へ 福島第一原発の今 〈原発事故 海水リアルタイムモニター〉(The Precise Data of Released Radioactivity Was Revealed).” NHK 40年後の未来へ 福島第一原発の今. The Japan Broadcasting Corporation , March 11, 2014. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/genpatsu-fukushima/20140311/index.html.

“平成20年版 福島県勢要覧(2010 The Data of Fukushima).” 平成20年版 福島県勢要覧 – 福島県ホームページ. Fukushima Prefectural Office, December 1, 2013. https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/sec/11045b/20058.html#3.

“放射線による健康影響等に関するポータルサイト(The Website Regarding Health Problem by Radioactivity).” 環境省_放射線による健康影響等に関するポータルサイト. Ministry of the Environment, 2018. https://www.env.go.jp/chemi/rhm/portal/.

“放射線による健康影響等に関する統一的な基礎資料(Unified Basic Data on Radiation Health Effects, Etc.).” 環境省_除染の方法. Ministry of the Environment, 2017. https://www.env.go.jp/chemi/rhm/h29kisoshiryo/h29kiso-09-01-03.html.

“福島原子力発電所事故による 農林水産業等への影響(The Aftermath of the Nuclear Disaster on the Primary Industries).” Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, April 15, 2011. https://www.maff.go.jp/j/shokusan/export/yunyukisei/pdf/besshi1.pdf.

“避難区域の変遷について-解説-(The Explanation of the Change of the Evacuation Areas).” 避難区域の変遷について-解説- – 福島県ホームページ. Fukushima Prefectural Office, April 11, 2023. https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/site/portal/cat01-more.html.

“風評に関する消費者意識の実態調査(第16回)について(The 16th Research on Consumer’s Attitude Regarding Bad Rumors for Nuclear Disaster).” Consumers Affairs Agency, Government of Japan, March 1, 2023. https://www.caa.go.jp/notice/entry/032410/.

Kana Sakamoto is a first-year student at Oberlin College studying as a Sociology Major. Her childhood memories of enjoying local cuisines throughout Japan and the world, as well as a four-month farming internship during gap term, have driven her into the connection between society, life, and food. Kana loves fried horse mackerel, consommé soup, and udon, all of which she is struggling to find in a small town in Ohio. Kana’s personal blog (in Japanese) can be found here: https://note.com/ka________7